Warriors Passage

Scout Trail

Warriors Passage National Recreation Trail

A Short History

James M. Wright, Sr., Knoxville, TN., November 2014

This account was prepared to document the research and work to locate and restore portions of an ancient trail from South Carolina into east Tennessee. The author is one of three Scout leaders, who over fifty years ago was involved in engaging their Boy Scouts during a period of three years in reopening this historic trail. Inactive in the Scouting program since 1985, he was surprised to learn of the continuing interest and work in maintaining the trail and of the number of Internet entries on this subject. The two true leaders of this endeavor, Dr. Paul Kelley and Mr. Harold Huffaker, are now deceased. To share his knowledge of events of fifty years ago he relied on notes he had kept on the trail restoration and records of Mr. Huffaker. It is being set forth before this information is lost and to honor his departed colleagues and the Scouts who cheerfully donated their labor.

The idea of incorporating an outdoor adventure and experience for Scouts along with a history lesson came from Paul Kelley, a Knoxville resident. Dr. Kelley, a noted educator, was also the Executive Secretary of the Fort Loudoun Association. The Association is the friends group for Fort Loudoun State Historic Area and as such is devoted to the restoration and operation of historic Fort Loudoun. The Organization was created by the Tennessee State Legislature in 1933 and operated Fort Loudoun independently until 1978 when Fort Loudoun became part of Tennessee’s State Park System. Dr. Kelley was also a Boy Scout leader, a role which was instrumental in bringing about “Warriors Passage".

From a historical perspective, there was knowledge of a trail from present day Charleston, SC to settlements on the Little Tennessee River and native towns in the Cherokee “overhills.” George Hunter had prepared a map in 1730 showing the ancient “Northwest Passage.” The “Waucheesi Trail” was a name sometimes used for the Passage in western North Carolina, while in eastern Monroe County, Tennessee, “Old Indian Trail” was a colloquial synonym in use until the trail or road over the mountains had been forgotten.

A camping place “on top of the mountains” had been described sufficiently in old accounts. A March 29, 1730 entry in Sir Alexander Cummings’ journal noted drinking some water from a spring there. In 1756, Captain Raymond Demere used the Passage, commanding a column of troops and artisans from South Carolina to begin the construction of Fort Loudoun to stop further French encroachment in the colonial backlands. His column was followed by pack horses carrying twelve cannons, weighing up to 300 pounds each, for the fort. Later journal entries noted good water on both sides of the mountain encampment site.

A search for the “Northwest Passage” which was the key terrain feature of the Charleston Path between present day Murphy, NC and Tellico Plains, TN and its importance to the full story of Fort Loudoun, had interested and engaged a number of historians, academies, and Monroe County residents spanning many decades. Research materials included old maps and accounts of early travelers. The best source was found in Benjamin Hawkins journal of 1797 describing his travels on the Charlestown Path on a visit to the western country. He kept meticulous records, mentioning many landmarks which are visible today. He left the following account: “We camped near the gap; there is good water on both sides that on the west is nearest the summit.” Members of the Association party knew of a pass that fitted Hawkins description and proceeded to Waucheesi Mountain within the Cherokee National Forest. The site was as Hawkins described it. There were distinct traces of an ancient path leading up the draws and crossing the knife-edge gap near the springs. From this site the general course of the Charlestown Path from the east across the Unicoi Mountains to the Little Tennessee valley could be visualized. The campsite was used for many years before the trail was abandoned about 1820 in favor of a wagon road using a different route.

Using the above sources, and contacts with long-time residents having knowledge of portions of the ancient path, the Fort Loudoun Association Subcommittee on Trails and Terrain submitted their report "Discovery in 1965 of First Commercially Used Road in Tennessee" to the Committee on Research, who forwarded it to the Association’s Board of Directors.

Most Scoutmasters are always looking for new and better hiking trails for their troops. Harold Huffaker, Scoutmaster of Troop 49 sponsored by Emerald Avenue United Methodist Church in north Knoxville, was no exception. Sometime during 1958, Dr. Paul Kelley mentioned the Northwest Passage to Huffaker (They were both members of the Church.) and how this would make a good trail, only if it could be located. Dr. Kelley was a good friend of many of the men who had collected the trail information. He was also Advisor of Boy Scout Post 49 and knew the value of a good trail.

Both men purchased maps of the area, obtained facts about the known portions of the trail, and then went on a field trip. It soon became apparent that the trail could not be used in its present condition. Long sections had been lost for many years and the existing sections were overgrown with trees and brush. It was also one of the wildest and most remote sections of east Tennessee. One encouraging fact was that the trail was within the Cherokee National Forest. This would mean that permission would not have to come from a great number of private land owners. The idea of clearing the trail survived for several years, even though it would require many hours of searching and back breaking work.

Jim Wright, Scoutmaster of Troop 252 sponsored by Inskip United Methodist Church, also in north Knoxville, was told of the trail. His troop also had many avid hikers and he was interested in the use of this trail. It was then decided that there was a possibility of locating the missing sections, cutting out the trees and brush, installing trail markers, and opening a new but very old trail for the current generation. There was now enough boy power combined to handle the job as well as the best research and information available.

The threesome decided to form a committee to facilitate project activities. They met in August 1963 and reached the following decisions as documented in their meeting minutes.

1. Before presenting the project to those who would be involved, it was decided that there would have to be a name for the trail. At this time it had been known as “Traders Path,” “Old Indian Trail,” “Northwest Passage,” and “The Soldiers Trail.” The new name of “Warriors Passage” seemed to fill the need. The warriors would include all the brave men who passed that way, both original inhabitants and later travelers. The word “passage” had been the earliest used and was retained.

2. Marking of the trail should be done with spray paint, avoiding the National Forest Service color code to prevent interference with their work.

3. Only their Scout units should be involved in the initial marking and clearing. Experienced Scouts would be used for the work.

4. A five stage program was planned for clearing the trail:

Stage one – Furnace Road to Wildcat Creek

Stage two – the campground

Stage three – Wildcat Creek to the campground

Stage four – campground to Moss Gap

Stage five – Roberts Farm near Unaka to Moss Gap

(The latter two stages were never undertaken)

5. The Fort Loudoun Association; the East Tennessee Historical Society; and the Great Smoky Mountain, Boy Scouts of America, would be asked to endorse the project. (By mid-October, all had given approval to the project.)

6. An award would be offered to Scouts who hiked the opened trail and camped overnight at the historic campground.

Later that year, Dr. Kelly presented to the Fort Loudoun Association Directors and the East Tennessee Historical Society Executive Committee the plan to clear the portion of the Charlestown Path that ran from what was now Unaka, NC to Tellico Plains, TN. The project committee met with United States Forest Service (USFS) representatives in mid-October at the Tellico Ranger Station to reveal their plans and to gain their approval to proceed with marking and clearing the trail. While there, the USFS offered to facilitate a trip to the twin springs campground over rough Forest Service roads.

Having gained all the requested approvals, written invitations were sent to those Scouts in the three units who had demonstrated to their leaders that they could do more than should be expected of a youngster. The first work on marking and clearing occurred in early November, 1963. The eagerness and enthusiasm was quite evident and everyone loaded into the cars, starting in Knoxville, for the trip to Tellico Plains (no Interstate at that time). Many preparations had been made and the party had everything they thought they needed to start work.

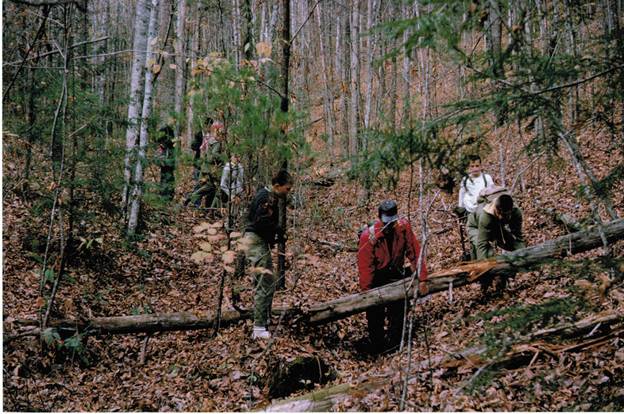

The last few miles of the trail that led into Tellico Plains had been covered by a USFS timber road (Old Furnace Road). The trail then left this little used road and followed a new timber road for a short distance. Then the party encountered what they had been wanting – the undisturbed woodland. Soon there were teams at work – some sawing, some pruning, some chopping, some digging, and the last ones removing the cuttings from the trail.

The Scouts wanted their trail to be like the Appalachian Trail on which they had hiked several times. There was some question as to just how much to cut along the trail. They had been taught not to cut anything unless there was a definite need. There was little trouble that first day as the trail location was generally known in this area. At the close of this first work day everyone had a feeling of satisfaction and a job well done. This did not seem to be as hard to do as first they anticipated.

This was the last chance to work on the trail in 1963 as the winter conditions seal the mountains off. There were three work days in 1964 and much more was learned about what needed to be done to succeed. At Wildcat Creek, about three miles from the end of the trail, the first major problem was encountered. Where did the trail cross the stream? The Scouts and their adult leaders fanned out in several directions looking for a trace of the old trail. There was a good description from old journals. The stream cut through a gorge with steep gray rock ledges as well as steep, thickly brushed earth banks. After several hours a Scout found traces of the old trail leading down to the stream and also leading up the other side from the crossing. This was their first major victory, the finding of the Wildcat Creek crossing.

There was much more to learn about the business of trail building. Patience was need as everything had to be checked again against detailed journal entries written by early travelers. A 1798 journal also noted crossing a small stream seven times. The restored trail followed this description.

The Scouts found that the most important tool was the long handled pruning hooks. This tool would cut everything up to one inch in diameter. The little buck saw and a sharp axe were also used a great part of the time. The work was not without incidences, most notably occasion encounters with fierce yellow jackets whose nests were being disturbed, and timber rattlesnakes found several times in the midst of the workers, thereafter requiring constant vigil.

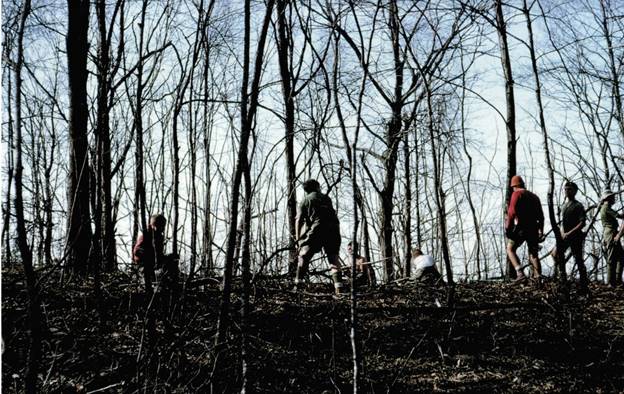

During the 1964 and 1965 work days much progress was made. There were several field trips by the adults who were attempting to keep the trail located just ahead of the Scouts. The work to locate the trail was time consuming and could hold back the Scouts who were anxious to cut their way through. By the end of 1964 it became evident that more time was needed each day for actual work. The long drive to the work sites and the return trip took four hours that could be used on the trail. In April 1965 a three day work camp was established about halfway to the historic campground so work could be done in both directions. With a work force of 17 Scouts and two adults, involving eight to ten hour work days, the trail had been located and cleared all the way to the old Twin Springs Camp. This had been the goal for two and one half years. The little boys who had started the project had grown to be big boys. Some of the Scouts were now old enough to join Post 49 and newly formed Post 300 at the Inskip Methodist Church in continuing their work.

The eight mile section of the trail that was restored started at the historic Twin Springs campground. To reach the campground the Scout leaders of the above units recommended hiking the trail, that started at Bald River Falls, for about 4.3 miles to a USFS road, then along the road for about 1.7 miles to Basin Gap, and then using another road up the mountain for about a mile to reach the campground. The total hike, using these routes, was about 15 miles, with the overnight camp at Twin Springs breaking it into about two equal day segments.

Thoughts then turned to an official trail dedication. Before then, the trail would have to be cleaned one final time as small vegetation can re-grow in one year’s time. The trail would have to be better marked and this would be a problem. There was no sponsor and therefore no funds. The Scouts agreed each to buy a sign and a post and install them.

The

Scouts had worked on the trail for four years (1963-1966). Thirty-six Scouts had contributed a total of 823 work hours. During all this time, Troop 49, Post 49, Troop 252, and Post 300 continued their other scouting activities on a very high scale.

Dedication of the trail took place on June 11, 1966 at the campground. Taking part in the ceremony were representatives from the Fort Loudoun Association, the Tennessee Historical Commission, the Warriors Passage Committee, and the National Forest Service. The latter provided transportation. The Scout units responsible for reopening the trail, along with Scouts from other troops, hiked in from Bald River Falls to be there to participate in the dedication and to camp overnight.

Wind was snapping the flags. A bugle was sounded and many of those in attendance thought of the bugles that had sounded there many years ago. One by one the speakers stood and told part of the Fort Loudoun/Warriors Passage story. This was the beginning again of something very old. Warriors Passage would again offer adventure to those who entered the wilderness.

In the absence of road access, the ceremony was not open to the public, but an article regarding the trail opening was featured the previous Sunday in the Knoxville News-Sentinel. There was possibly other local coverage. The January 1967 issue of Boys Life, with a circulation of nearly 2 ½ million, contained an article with photos of the trail.

At the end of 1966, over 400 Scouts from 29 troops in Tennessee, Georgia, and Mississippi had completed this historic outdoor adventure. In 1967, about 475 Scouts from 34 troops followed.

During this time the perils of having a trail in a national forest were realized. Hiking along the “completed” trail it was noted that logging operations and construction of access roads for timber removal damaged or obliterated sections of the restored trail requiring re-cleaning or relocation of those segments, and replacement of trail signs that had been removed by the contractors. Maintenance by the Scouts continued in 1967 and for years thereafter. A February 1971 Committee newsletter reported that over 2,000 Scouts had hiked the trail and camped overnight at Twin Springs. At least eleven troops hiked and camped in 1971, the last year detailed records were apparently kept.

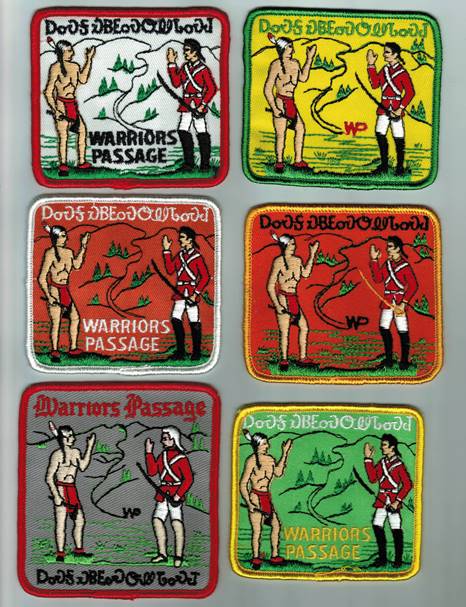

Young boys like to earn awards for their achievements. The Warriors Passage Committee created a patch that could be earned and worn on their Scout shirt for hiking the trail, camping overnight at the Twin Springs campground, and demonstrating some historic knowledge regarding this adventure. To facilitate this outdoor adventure, the Committee developed a brochure on the trail that included its history, a map, and other guidance for Scouts and their leaders. A medal was considered in lieu of a patch but was rejected because it might conflict with other medals that Scouts could earn. The “original” patch is shown below at the top left. Over the years several different color combinations were created, but the two “warriors” and the background remained, as did the inscription across the top which spelled “Brave Man’s Trail” in the Cherokee language. “Trail” in that language means also “where he comes.”

This writer moved from Knoxville in mid-1968 to Madison, WI and two years later to Minnesota resulting in limited correspondence with Messrs Kelly and Huffaker until he returned to Knoxville in 1978. A new Troop 252 was formed under his leadership and a trail maintenance project was carried out by the troop in October 1979, followed by others in 1980, 1982 and 1984. In an April 1984 letter to Mr. Huffaker, this writer stated that after hiking the trail with some of his Scouts, the campground and trail were in real good shape. There were likely other trail maintenance activities by Troop 49 and Post 49 before and during this period, but there are no known records.

“Retiring” as a Scout leader in 1985, there was no further involvement in Warriors Passage. Although there were many luncheons and other activities with Messrs. Kelly and Huffaker, until their deaths a few years ago, the subject of the trail was never raised. An opportunity was foregone to learn how long the Scouts maintained the trail and its use by other Scout troops as an outdoor adventure.

Contact the Webmaster